About the Project

The Hampson Archeological Museum State Park collection represents one of the world's most extraordinary collections of American Indian artistic expression as well as a major source of data on the lives and history of late pre-Columbian peoples of the Mississippi River Valley. The collections at the museum are the result of extensive excavations of the Nodena Site as well as excavations at other sites in the region by Dr James K. Hampson, and work by others including the University of Alabama and the University of Arkansas.

While the museum and its collections are well known in select archeological circles, its extraordinary materials are not widely known. The Virtual Hampson Museum Project was initiated to improve the visibility and accessibility of these materials – making them more available to both public and scholars. The Virtual Hampson Museum was completed by CAST in 2010 and was the first of its kind to make a large collection of 3D digital objects publicly accessible. The project was made possible through the generous financial support of the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council and the assistance of the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, the Arkansas Department of Heritage, and the Arkansas Archeological Survey.

The Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resource Council was established in 1987 to manage and distribute grants from the Natural and Cultural Resources Grants and Trust Fund. The fund is managed for the acquisition, management, and stewardship of State-owned lands, or the preservation of State-owned historic sites, buildings, structures, or objects which the ANCRC determines to be of value for recreation or conservation purposes. said properties to be used, preserved, and conserved for the benefit of present and future generations.

Digital Reuse of the Hampson Digital Collection

There are many rationales for the creation of digital representations of cultural heritage materials. Among these are preservation of a representation when the original may be repatriated or otherwise accessible, increased access since physical travel is not needed, increased capabilities for various digital metrical analyses, increased opportunities for comparative analyses, potential for 3D printing of objects for class and public use, and more. From the scholarly community’s perspective, perhaps one of the most compelling, is the linked aspects of reproducibility and reuse. Freely accessible digital objects can readily be reused in analyses by other researchers allowing them to conduct repeated studies. The broader situation has been well summarized by Shiri (2017):

The implications of using, reusing and repurposing digital content and collections, in this open and information rich environment, are profound and multifaceted, cutting across many different institutional contexts such as libraries, archives and museums, as well as numerous disciplines and a wide range of user communities and audience types. Access to digital libraries, in particular, has been closely associated with and discussed in regards to such measures of impact, value and usefulness.

Within archaeology and cultural heritage in 2018 an entire issue of the journal Advances in Archeological Practice (2018:6(2)) focused on digital reuse.

Since its initial publication in 2010 the Hampson Virtual Museum collection has seen remarkable digital reuse. We have identified more than 40 articles and chapters where the Hampson digital materials have been reused in analysis and research. The primary role of the materials has been in the development and assessment of digital analytical methods to study archeological/cultural heritage collections and well as the broader computer science issues of 3D object identification and search. Early on the collection was seen as valuable reference set for scientists developing techniques for object identification and search, particular by scholars in the European Union. In 2016 the Hampson materials were made part of the Shape Retrieval Contest (SHREC) collection. This is a collection of 3D objects that is used to assess and validate various 3D retrieval methods. A contest is held every year in association with the Eurographics Conference.

With the updates to the Virtual Hampson Museum website in 2019, the project team made the decision to remove the ability to download the 3D object models. While we have seen remarkable research and scholarly endeavors using the virtual collection, we have also witnessed misuse of the 3D models and violations of our clearly stated Creative Commons licensing. Under the original licensing, it was stated that the models were not to be used for commercial purposes without the express written approval of the Quapaw tribe, the most commonly recognized descendant population. As technology evolved rapidly in the decade after initial publication, our ideas regarding digital model ownership also evolved, and we became more aware of cultural sensitivities associated with some of the objects in the collection. For these reasons, we removed the ability to download the objects and transitioned to the 3DHOP viewer for direct viewing and manipulation of objects in browser.

The Virtual Hampson Museum in the Literature

Agosto, Eros, and Leandro Bornaz. 2017. “3D Models in Cultural Heritage: Approaches for Their Creation and Use.” International Journal of Computational Methods in Heritage Science (IJCMHS) 1 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCMHS.2017010101

Andreadis, A., R. Gregor, I. Sipiran, P. Mavridis, G. Papaioannou, and T. Schreck. 2015. “Fractured 3D Object Restoration and Completion.” In ACM SIGGRAPH 2015 Posters, 74:1–74:1. SIGGRAPH ’15. New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2787626.2792633

Biasotti, Silvia, Andrea Cerri, Chiara Catalano, Bianca Falcidieno, Maria Torrente, Stuart Middleton, Leo Dorst, Ilan Shimshoni, Ayellet Tal, and Dominic Oldman. 2016. “Report on Shape Analysis and Matching and on Semantic Matching.” Monograph. March 16, 2016. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/392697/

Biasotti, Silvia, Andrea Cerri, Bianca Falcidieno, and Michela Spagnuolo. 2015. “3D Artifacts Similarity Based on the Concurrent Evaluation of Heterogeneous Properties.” J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 8 (4): 19:1–19:19. https://doi.org/10.1145/2747882

Campetti, Casey, Maija Glasier-Lawson, Matthew Kalos, Hilary Miller, Megan Springate, Stephanie Sullivan, and Katie Turner. 2014. Interpretative actions for archeological resources. Park Break Perspectives. The George Wight Society. Handcock, MI. 19 pgs

Cook, Matt. 2018. “Virtual Serendipity: Preserving Embodied Browsing Activity in the 21st Century Research Library.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 44 (1): 145–49

Dimou, Dimitrious. 2018. “Identifying 3D Objects from Maps Depth.” MA Thesis, Greece: Polytechnic School, University of Patras, Municipality of Dimitrios. Greece

Dimou, D. and K. Moustakas, “A Framework for 3D Object Segmentation and Retrieval Using Local Geometric Surface Features,” in 2018 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW), 2018, 102–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/CW.2018.00028

Felicísimo, Ángel M., María-Eugenia Polo, and Juan A. Peris. 2013. “Three-Dimensional Models of Archaeological Objects: From Laser Scanners to Interactive Pdf Documents.” Technical Briefs in Historical Archaeology 7: 13–18

Freeman, Mark. 2015. “‘Not for Casual Readers:’ An Evaluation of Digital Data from Virginia Archaeological Websites.” Masters Theses, August. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3476

Gregor, Robert, Danny Bauer, Ivan Sipiran, Panagiotis Perakis, and Tobias Schreck. 2015. “Automatic 3D Object Fracturing for Evaluation of Partial Retrieval and Object Restoration Tasks - Benchmark and Application to 3D Cultural Heritage Data.” The Eurographics Association. https://doi.org/10.2312/3dor.20151049

Gregor, Robert, Christof Mayrbrugger, Pavlos Mavridis, Benjamin Bustos, and Tobias Schreck. 2017. Cross-Modal Content-Based Retrieval for Digitized 2D and 3D Cultural Heritage Artifacts. The Eurographics Association. https://doi.org/10.2312/gch.20171302

Ioannakis, George, Anestis Koutsoudis, Fotis Arnaoutoglou, Chairi Kiourt, and Christodoulos Chamzas. 2017. “On Structure-From-Motion Application Challenges: Good Practices.” International Journal of Computational Methods in Heritage Science (IJCMHS) 1 (2): 47–57. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCMHS.2017070103

Kaimaris, Dimitris, Charalampos Georgiadis, Petros Patias, and Vassilis Tsioukas. 2017. “Aerial and Remote Sensing Archaeology.” International Journal of Computational Methods in Heritage Science (IJCMHS) 1 (1): 58–76. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCMHS.2017010104

Kiourt, Chairi, Anestis Koutsoudis, Fotis Arnaoutoglou, Georgia Petsa, Stella Markantonatou, and George Pavlidis. 2015. “A Dynamic Web-Based 3D Virtual Museum Framework Based on Open Data.” In 2015 Digital Heritage, 647–50. Granada, Spain: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DigitalHeritage.2015.7419589

Kiourt, Chairi, Anestis Koutsoudis, and George Pavlidis. 2016. “DynaMus: A Fully Dynamic 3D Virtual Museum Framework.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 22 (November): 984–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.06.007

Koutsoudis, Anestis, and Christodoulos Chamzas. 2011. “3D Pottery Shape Matching Using Depth Map Images.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 12 (2): 128–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.12.003

Koutsoudis, Anestis, George Ioannakis, Ioannis Pratikakis, and Christos Chamzas. 2015. “RETRIEVAL 3D: An On-Line Content-Based Retrieval Performance Evaluation Tool.” The Eurographics Association. https://doi.org/10.2312/3dor.20151062

Koutsoudis, Anestis, George Pavlidis, Vassiliki Liami, Despoina Tsiafakis, and Christodoulos Chamzas. 2010. “3D Pottery Content-Based Retrieval Based on Pose Normalisation and Segmentation.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (3): 329–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.02.002

Koutsoudis, A., G. Pavlidis, and C. Chamzas. 2010. “Detecting Shape Similarities in 3D Pottery Repositories.” In 2010 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Semantic Computing, 548–52. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSC.2010.50

Koutsoudis, Anestis, Ioannis Pratikakis, and Christodoulos Chamzas. 2013. “On 3D Object Retrieval Benchmarking.” 3D Research 4 (4): 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/3DRes.04(2013)3

Limp, Fred, Angelia Payne, Katie Simon, Snow Winters, and Jackson Cothren. 2011. “Developing a 3-D Digital Heritage Ecosystem: From Object to Representation and the Role of a Virtual Museum in the 21st Century.” Internet Archaeology 30

Limp, William Fred. 2016. “Measuring the Face of the Past and Facing the Measurement.” In Digital Methods and Remote Sensing in Archaeology, 349–369. Springer

Максимова, Татьяна Евгеньевна. 2013. “Виртуальные Музеи vs Традиционные Музеи: Преимущества Виртуальных Экспонатов.” Исторические, Философские, Политические и Юридические Науки, Культурология и Искусствоведение. Вопросы Теории и Практики, no. 4–3: 109–111

(Maximova, Tatyana Evgenievna. 2013. “Virtual Museums vs Traditional Museums: The Benefits of Virtual Exhibits.” Historical, Philosophical, Political and Legal Sciences, Cultural Studies and Art History. Questions of theory and practice, no. 4–3: 109–111.)

Papaioannou, Georgios, Tobias Schreck, Anthousis Andreadis, Pavlos Mavridis, Robert Gregor, Ivan Sipiran, and Konstantinos Vardis. 2017. “From Reassembly to Object Completion: A Complete Systems Pipeline.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 10 (2): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3009905

Pavlidis, George, Anestis Koutsoudis, Fotis Arnaoutoglou, Vassilios Tsioukas, and Christodoulos Chamzas. 2007. “Methods for 3D Digitization of Cultural Heritage.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 8 (1): 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2006.10.007

Pratikakis, I., M. Spagnuolo, T. Theoharis, L. Van Gool, and R. Veltkamp. 2015. “Partial 3D Object Retrieval Combining Local Shape Descriptors with Global Fisher Vectors.”Eurographics Workshop on 3D Object Retrieval (2015) I. Pratikakis, M. Spagnuolo, T. Theoharis, L. Van Gool, and R. Veltkamp (Editors)

Pratikakis, Ioannis, Michalis A. Savelonas, Pavlos Mavridis, Georgios Papaioannou, Konstantinos Sfikas, Fotis Arnaoutoglou, and Dirk Rieke-Zapp. 2018. “Predictive Digitisation of Cultural Heritage Objects.” Multimedia Tools and Applications 77 (10): 12991–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4928-y

Pratikakis, I., M. A. Savelonas, F. Arnaoutoglou, G. Ioannakis, A. Koutsoudis, T. Theoharis, M. T. Tran, et al. 2016. “SHREC’16 Track: Partial Shape Queries for 3D Object Retrieval.” In Eurographics Workshop on 3D Object Retrieval. http://ralph.cs.cf.ac.uk/papers/Geometry/shrec16.pdf

Raffo, A., and S. Biasotti. 2016. “Calcolo Di Descrittori Ibridi Geometria-Colore per l’analisi Di Similarità Di Forme 3D.”

Rizvic, Selma. 2014. “Story Guided Virtual Cultural Heritage Applications.” Journal of Interactive Humanities 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.14448/jih.02.0002

Santamaría, José, Enrique Bermejo, Carlos Enríquez, Sergio Damas, and Óscar Cordón. 2017. “New Application of 3D VFH Descriptors in Archaeological Categorization: A Case Study.” In International Joint Conference SOCO’17-CISIS’17-ICEUTE’17 León, Spain, September 6–8, 2017, Proceeding, 229–236. Springer

———. 2018. “New Application of 3D VFH Descriptors in Archaeological Categorization: A Case Study.” In International Joint Conference SOCO’17-CISIS’17-ICEUTE’17 León, Spain, September 6–8, 2017, Proceeding, edited by Hilde Pérez García, Javier Alfonso-Cendón, Lidia Sánchez González, Héctor Quintián, and Emilio Corchado, 229–36. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Springer International Publishing

Sateila, Heikki. 2011. “Kolmiulotteisen Kulttuuriperintökohteen Digitointiprosessi.”

Savelonas, Michalis A., Ioannis Pratikakis, and Konstantinos Sfikas. 2014. “Fisher Encoding of Adaptive Fast Persistent Feature Histograms for Partial Retrieval of 3D Pottery Objects.” In 3DOR. https://doi.org/10.2312/3dor.20141051

———. 2015. “Partial 3D Object Retrieval Combining Local Shape Descriptors with Global Fisher Vectors.” In Eurographics Workshop on 3D Object Retrieval, edited by I. Pratikakis, M. Spagnuolo, T. Theoharis, L. Van Gool, and R. Veltkamp. The Eurographics Association. https://doi.org/10.2312/3dor.20151051

———. 2016. “Fisher Encoding of Differential Fast Point Feature Histograms for Partial 3D Object Retrieval.” Pattern Recognition 55 (July): 114–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2016.02.003

Schreck, Tobias. 2017. “What Features Can Tell Us about Shape.” IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, no. 3: 82–87

Sfikas, Konstantinos, Ioannis Pratikakis, Anestis Koutsoudis, Michalis Savelonas, and Theoharis Theoharis. 2013. “3D Object Partial Matching Using Panoramic Views.” In International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing, 169–178. Springer

Sipiran, Ivan. 2017. “Analysis of Partial Axial Symmetry on 3d Surfaces and Its Application in the Restoration of Cultural Heritage Objects.” In The IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Vol. 2

Tsiafaki, Despoina, and Natasa Michailidou. 2015. “Benefits and Problems through the Application of 3D Technologies in Archaeology: Recording, Visualization, Representation and Reconstruction.” Scientific Culture 1 (3): 37–45

Вавулин, Михаил Викторович, Ольга Викторовна Зайцева, and Андрей Александрович Пушкарев. 2014. “Методика и Практика 3D Сканирования Разнотипных Археологических Артефактов.” Сибирские Исторические Исследования, no. 4

(Vavulin, Mikhail Viktorovich, Olga Viktorovna Zaitseva, and Andrei Alexandrovich Pushkarev. 2014. “Methods and Practices of 3D Scanning of Different Types of Archaeological Artifacts.” Siberian Historical Research, no. 4)

Zherebyatiev, Denis, Maxim Demidov, Svetlana Koroleva, Danila Driga, Victoria Morozova, and Daniil Pashkovski. 2015. “Experiences of the Digitization of Museum Collections through Technology Laser Scanning and Photogrammetry for the Project Portal of Culture of the Russian Federation?” In EVA

The Virtual Hampson Museum project brings together a number of innovative approaches to the capture and distribution of digital information. While the technology used for this project was cutting edge at the time of initial data acquisition, more modern systems are able recreate 3D models in even greater detail. This section provides an overview of how the data was initially acquired in 2009 and how the process works

Scanning and Creating a Digital Object

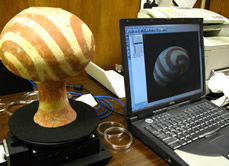

In the Gallery section of this web site you can view digital representations of many of the objects in the Hampson Archaeological Museum located in Wilson, Arkansas. The objects were digitized using the Konica-Minolta VIVID 9i 3D scanner. The Vivid 9i is a short-range 3D scanner best suited for capturing moderate detail of objects no larger than a beachball. The scanner also has an onboard VGA camera that captures color during the scan process resulting in a photo-realistic, 3D digital model like those shown in the Virtual Hampson collection.

Objects were placed on a calibrated turntable to automate the data collection process. In addition, a professional lighting system, similar to that used for product photography, was used to facilitate accurate color capture. The 3D models were processed using Polyworks or Rapidform XOR (now Geomagic Design X).

How Precise are the Models?

The precision of data collected via a laser scanner can be extraordinary. The scanner used in this project, a Minolta-Konica Vivid 9i, can record the x, y and z location of the surface of an object within a range of plus or minus 0.05 mm (50 µm) and can measure the z dimension with an precision of plus/minus 0.008 mm (8 µm). For comparison a typical human hair is around 0.05 mm (50 µm).

These specifications are contingent upon factors such as the distance at which the object was scanned, the surface reflectivity, the diaphaneity of the object, and the amount of ambient light. The published specifications for this equipment are the “best” possible while using the scanner’s “tele” lens. For most of the scanning in the Hampson Museum, the scanner was used with its “middle” lens. This allows a larger area to be scanned at one time but reduces the precision and accuracy. As the digital data was processed, multiple individual scans were merged together as discussed above. This process brings together some points that were very precise with others that were less. The completed 3D data object typically will have a precision of about 0.2 millimeters.

Displaying the Models

The latest version of the Virtual Hampson Museum displays the digital objects using 3DHOP (3D Heritage Online Presenter). 3DHOP is an open source 3D object viewer developed by the Visual Computing Lab of the Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologie dell’Informazione (Institute of Information Science and Technologies, or ISTI). Developed with an eye towards the Cultural Heritage field, 3DHOP allows the seamless integration of 3D models into a standard web page without the need for plugins or downloads.

More information can be found at the 3DHOP homepage and this publication:

3D Heritage Online Presenter

Marco Potenziani, Marco Callieri, Matteo Dellepiane, Massimiliano Corsini, Federico Ponchio, Roberto Scopigno

Computers & Graphics, Volume 52, November 2015, Pages 129-141, ISSN 0097-8493

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2015.07.001

Nodena, refers to a time, a place, and a people...

...an appreciation of these amazing artifacts is intrinsically linked to an understanding of where and when these objects were created, and by whom.

The Place

The central Mississippi valley encompasses low-lying areas adjacent to the Mississippi River in present-day Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee. It is bounded on its eastern margin by the Loess Bluffs of Tennessee and on the west by Crowley’s Ridge in Arkansas.

By the late prehistoric period (the early 1500s, just prior to Spanish explorers entering the vicinity), the Central Mississippi River Valley was home to numerous Native American Indian groups living in towns throughout the area. The remains of several of these towns were investigated by Dr. James K. Hampson in the early 1900s. Two of these former prehistoric villages were located on Nodena, his family’s farm, and became known as the Upper Nodena and Middle Nodena archeological sites. Archeological investigations at these sites have since yielded knowledge about the Native American Indians who lived there.

The Time

The Central Mississippi Valley has a long history of human occupation, dating back to at least 12,000 years ago, and continuing to the present day. Throughout this long time period, the lifestyles, daily activities, and beliefs of the people who lived here have changed. Over time, these changes manifested themselves in ways that serve to define the particular culture responsible for them. These cultures are defined over a geographic area and the time period in which they existed. Culture areas can be further refined by archaeologists into phases, which refer to smaller, sub-areas of a particular cultural group during a specific span of time within an area.

The archeological remains of the Native American groups that were living in the northwestern portion of the Central Mississippi Valley (an area that today includes northeastern Arkansas and the Bootheel of Missouri) from about 1450 to 1650 AD are referred to by archaeologists as the Nodena phase, named after the archeological sites on the Hampson farm.

The People

We do not know what the inhabitants of the Central Mississippi Valley called themselves prior to the time of European contact. They may have been a part of the “Province of Pacaha” mentioned in the 1541 chronicles of the Hernando de Soto expedition through eastern Arkansas. Some archeologists equate the Nodena phase with Pacaha.

The Nodena people were farmers, growing corn, beans, and squash, as well as tending and collecting a wide range of wild plant foods. They hunted a variety of local wildlife, especially white-tailed deer and migratory waterfowl, and caught large quantities of fish in oxbow and seasonal lakes. Some Nodena towns may have been surrounded by a ditch or a combination of a ditch and palisade wall. Towns consisted of closely spaced houses, as well as smaller structures for storing corn, drying meat, or preparing animal hides. The focus of larger Nodena settlements was one or more rectangular, flat-topped earthen mounds that supported civic and religious buildings. Throughout the Central Mississippi Valley and the greater Midsouth, the prehistoric houses were square and constructed of timbers set into trenches in the ground. Lengths of cane were “woven” between these timbers and the resulting walls were sealed with packed clay, a technique referred to as “wattle and daub.” House floors were also packed with clay to produce a flat living surface. A centrally located hearth provided warmth and a cooking fire. Dr. Hampson excavated a number of such houses at the Upper Nodena site.

The Nodena people fashioned tools and implements from stone, wood, bone, antler, and shell. Their arrows were tipped by small willow leaf-shaped points, dubbed by archaeologists as the Nodena point type. They also made a wide variety of implements for gardening and hide preparation. Woodworking and basketry were common endeavors for the Nodena people, and they created ornamental objects from bone, shell, and stone. Ceramics were produced by mixing local backswamp clays tempered with crushed mussel shell. Some of the ceramic vessels by the Nodena people and their neighbors were quite artistic, including painted red and white swirls, complex incised designs (such as portraits of mythical figures), and modeled effigy vessels representing people and various animals. Most of the ceramic vessels in Dr. Hampson’s collection probably were not made for utilitarian (everyday) use, but rather for ritual use, including burial with the dead.

The Nodena people may have been the ancestors of the of the modern-day Quapaw Tribe, who in the late seventeenth century, had several towns around the confluence of the White and Arkansas Rivers. The Quapaw maintained a presence in the area until their removal to northwest Louisiana in 1824, when all of their land in the Territory of Arkansas was ceded to the United States. In 1834, under another treaty, they were forcibly relocated to their present location in the northeastern Oklahoma. Present-day descendants of the Quapaw people are members of the Quapaw Tribe of Indians.

Suggested readings:

Who is Hampson?

The amazing materials at the Hampson Museum State Park were made possible by the efforts and dedication of Dr. James K. Hampson. He was born in Memphis, Tennessee on July 9, 1877 and graduated from the College of Medicine, now the Medical School at the University of Tennessee in 1898. Dr. James K. Hampson then attended the New York Polyclinic School and went on to practice medicine for over 25 years in Memphis, and in Arkansas at Nodena and Fort Smith. Dr Hampson died on October 8, 1956.

Dr. Hampson coupled his interest in science and background in medicine with an interest in archaeology and this resulted in the excavation of over 1,000 burials at Nodena alone. Dr. Hampson took great care to ensure that the materials he found were not scattered far and wide into various public and private collections as was common with other sites in the region at the time. Additionally he worked with a number of professional archaeologists including Walter B. Jones of the Alabama Museum of Natural History; Samuel C. Dellinger of the University of Arkansas, who Hampson generously permitted to excavate Nodena; and Stephen Williams of Harvard, who Hampson permitted to extensively study his collection in 1953.

Modern Arkansas laws now make the disturbance of human burials without a permit illegal and permits are issued only when impacts from construction or other damage are unavoidable. However, in the first half of the 20th century, excavation of human remains was unfortunately all too common. While other excavators in this time were often not much better than looters, Dr. Hampson carried out his work with care and attention, drawing on his medical training and experience, and collaborating with professional archaeologists. According to Williams, “Dr. Hampson brought an inquiring mind and a sound knowledge of the scientific method to the subject of archaeology… his methods equaled those of his professional colleagues working in the area at the same time.”

For more on Dr. Hampson see:

Williams, Stephen 1957 James Kelley Hampson 1877-1956. American Antiquity 22(4):398-400

Mainfort, Robert 2008 James Kelley Hampson (1877-1956). Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture.

Morse, Dan. F. (ed) 1989 Nodena. Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series 30. Fayetteville, AR