3D Nodena Village

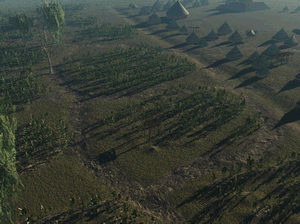

In this section of the Virtual Hampson Museum you will find a series of images that have been created using the latest computer visualization techniques. The goal of these images is to give you a better sense of what the site might have looked like some 500 years ago. We can never be certain how the village appeared, but we have pulled together information from archaeological investigation, traditional sources, and historical record. Please be sure and explore the Nodena Village Overview for more information on how the details of the visualizations were determined.

We hope that these images increase your interest and curiosity about this location and the people of Nodena ,who may have been the ancestors of the modern Quapaw. Our ideal goal would be to create an image, that if given to a Nodena Villager, would have them say “yes, that is what it looked like.” Of course, this goal is impossible, but it is an ideal that we keep in mind. Nodena was the home for many people and we hope that these images can begin to provide a sense of the richness and complexity of their lives and engage your interest to learn more about the creators of the amazing objects in the Virtual Hampson Museum.

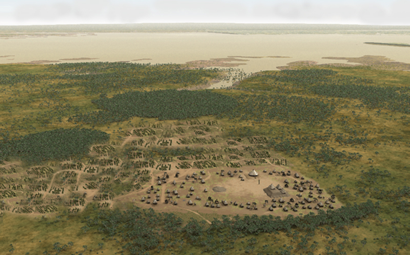

The Upper Nodena Village Visualization

The Upper Nodena Site was a well-demarcated town or village occupying an area of approximately 15.5 acres. It is located on a relict channel of the Mississippi River in northeastern Arkansas and is considered to be a late period Mississippi Valley site, suggesting a period of occupation between A.D. 1400-1600. There is some evidence that the town was enclosed by a ditch. It consisted of a ceremonial or 'corporate' complex of two pyramidal mounds, a burial mound, and (possibly) a plaza connecting the mounds, and a chunkey field. Dr. Hampson reported a chunkey field that is located south of Mound A and a large plaza, or public square, is located to the west. Houses and cemeteries surrounded the ceremonial area; larger structures situated nearer the complex. Based on the known number of human burials at the site, archaeologists estimate that the town’s population was between 1000 and 1500 at any given time during its 100 years of occupation.

The village also included nearby agricultural fields and groves. The residents of the town practiced maize and bean agriculture, and they consumed many local wild plants, such as hickory nuts, black walnuts, hazelnuts, persimmon, wild cherry, and paw paw in their diets. They also hunted deer, bear, raccoon, rabbit, turkey, waterfowl, and fish.

Representative of the ‘material wealth’ of the inhabitants of the town is the extensive collection of artifacts that have been recovered from the site. The beautiful Nodena effigy and decorated pottery are among the most outstanding examples of Native American art anywhere in the world. We encourage you to Browse the Virtual Collection of Nodena pots

Read more on the rules and decisions made in the creating the Nodena Village Visualizations in the Nodena Village Overview

The Ceremonial Structures

The locations of the ceremonial structures at Nodena are taken from a village plan developed by Dr Hampson. The largest structure, Mound A, was a pyramidal mound measuring approximately 120 x 111 feet, 15 feet tall, and oriented east and west. It was described as having two levels; perhaps containing buildings. Other mounds surround Mound A and vary in size from 1.5 to 4 feet tall measuring up to 75 to 100 feet in diameter and may have been primarily residential in nature. Mound B, a partially excavated platform mound, was originally described as supporting a structure 60 feet in diameter, although we lack convincing archaeological evidence for this description. Mound C, southwest of Mound A, is the only known burial mound at the site and is recorded as being approximately three feet high and 75 feet square. A chunkey field is located south of Mound A, and a large plaza or public square, is located to the west. Read more about the details of the ceremonial structures and other areas in the Ceremonial Structures.

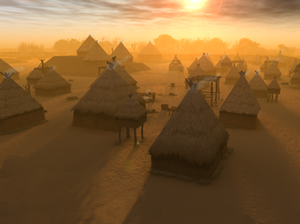

The Houses and other Structures

Houses at the Nodena site were rectangular; ranging in length from 10 to greater than 25 feet on their long axis, or square; ranging in size from 10 to 13 square feet. Historical sources were used in generating the appearance of the houses, the characterization of the wall surfaces, and construction details. Small stilted structures that dot the neighborhoods in the (re)creation are corn cribs and the shorter pole structures are drying or smoking racks and hide stretchers. Summer kitchens that provide shade in the summer heat are represented by roofed pole structures. Read more about the construction details of individual Nodena Structures in the FAQ Section.

Agricultural Fields and Surrounding Vegetation

The nature of the trees and forest in the area of the Nodena Village was the result of the area’s natural conditions as well as 1,000s of years of “forest management” by the inhabitants of the area. It has become clear in the last decades that the Native Americans actively managed the forest throughout the continent. The Nodena people cleared areas for farming, often leaving nut and fruit-bearing trees for foraging. Read more about how vegetation and fields were "placed" in the FAQ pages on Fields and Vegetation

What were the “rules” for the (re)creation of the Nodena Site?

In creating a single image many specific decisions had to be made. In creating a house, for example, we need to decide how tall the walls are to be, how thick they were, what color they were and so on. The same is true for all aspects of the recreation. In the following we attempt to provide the basis for each of the decisions that were made. These include historic records, traditional community knowledge and archeological data.

We want to call particular attention to the use of the historic resources. It is inappropriate to automatically presume that a description of a house made in (say) 1780 in southern Louisiana is in any way similar to a house constructed in northeastern Arkansas in the 1400 or 1500s. Among other things, the introduction of metal woodwork tools, had a dramatic effect on construction methods as did all the various dislocations and changes due to disease, conflict, and other factors that affected the Indian communities from the early 1500s on to today. Many of the Europeans recording these historic details commonly had negative racial-based stereotypes about Native Americans, and these can affect even simple descriptions of house construction or agricultural methods. We must be aware of these biases and do what we can to understand the reality that lay behind them.

Another important source is traditional knowledge from various Indian communities. In this we draw upon artistic traditions, art styles, narratives, and other sources. This is an area of the FAQ page that we hope to grow much more over time.

Archeological data is an important source, but it also has its limitations. Under fortunate circumstances, for example, it may be possible to find the evidence for a structure’s foundation, so we can determine how large a house might be, but this does NOT (usually) give us guidance on how tall the walls were, the nature of the roof structure or other similar archeologically “invisible” factors. We have made a conscious decision to be strongly directed by the archeological data, but not limited by it. If we only (re)created elements of the site that were known from archeological data, we would provide an image that was scientifically “accurate,” but clearly untrue and not authentic. We would be forced to leave out many things that we can be certain were present, such as cooking areas, drying racks and many other items of everyday life that were present but not preserved or discovered in the archeological record. In an ideal world we would want to give our images to a Nodena villager who would agree that these “looked like her home.” Of course, this is impossible -- but we keep this ideal in mind.

Our solution has been to evaluate all of the various lines of evidence and inferences and to carefully aggregate of all these sources. In any event we have provided the basis for these decisions below.

It is also important to remember that any image is just one of many possible images. The evidence and the sources do not usually provide a single, unequivocal answer. Often there are two, or more, different possibilities. Fortunately, the computer visualization techniques that we have used provide a great deal of flexibility. Once we have created a single house it is then possible to ask the software to place one, a dozen, or even 100 across the area. Over the next year we will be adding to what we have already created and hope to present some alternative ideas about the rich and complex world that was this Nodena Village some 500 years ago.

Nodena Village Overview - What was the basis for the elements in the main village images?

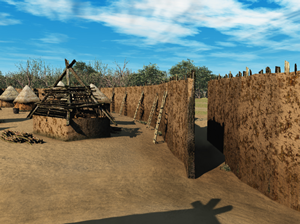

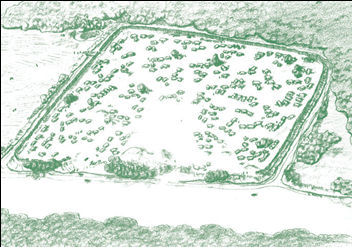

Was there a ditch, palisade or neither?

At Nodena, Morse notes that the village limits correspond closely with swales or “drainage ditches” (1989:101) and concludes that the evidence “suggests a palisade wall and ditch.” Mainfort, however, concludes that there was not a palisade (2007:120) and indicates that seismic trenching in the area supports this conclusion. Dr. Hampson described the site as surrounded by a ditch (1989) but Mainfort reports that there has been no archeological confirmation of this. The Nodena Village in the main village (re)creations has been shown without a ditch or palisade. However, we have also elected to create a few images that depict the village with a palisade. The presence or absence of the ditch and/or palisade probably had a strong influence on the density of structures “inside” the village. In general, palisaded villages had a much denser distribution of structures that did non-palisaded ones (see the Cherokee example mentioned above).

A palisade is a series of logs placed vertically in the ground to create a walled fortification around the village. Palisaded villages were common in northeastern Arkansas when the Spanish traveled there in the 1540s. A well-known example is the Parkin Site (now an Arkansas State Park – see illustration). In fact, Hudson says that the Spanish may have visited the area of the Nodena Site. While these fortified villages were common, it was also the case that many villages were not. In general, the presence of a palisade likely indicates that the area was subjected to warfare or other conflict. In the 1700s for example, Creek and Cherokee villages consisted of many separate houses scattered over a large area, each with their own fields (Waselkov 1991:85) with no fortifications. Some other examples of palisaded villages can be found at:

https://www.nps.gov/history/seac/beneathweb/ch9/f75.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chromesun_kincaid_site_01.jpg

What was the extent of the village?

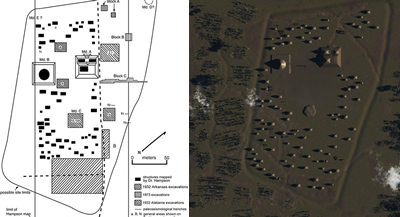

We based our extent of the village on the Hampson (1989) map shown to the bottom right. Specifically, the locations of the three main mounds (Mound A, B, and C), the plaza and chunkey court area, and the boundary ditch were derived from this map.

How did you determine the number of houses?

Hudson (1997:289) states that villages in northeast Arkansas had 15 to 40 houses and that the Nodena site had an estimated 1,000 – 1,500 people (1997:295). Morse also (1989) estimates the population at between 1,000 and 1,500. According to the Hampson map to the right, there are 66 houses shown in the excavated areas of the site (Morse 1989:98, Mainfort 2005:26-27). As not all the site was excavated it is very likely that similar numbers of houses were present in the unexcavated area and we have extrapolated them into these areas. In the current set of visualizations, there are 82 houses across the entire site. In a future version of the project we will be creating a number of alternative images that will illustrate possible variations in site population as well as site density.

How did you locate the houses?

The locations of the 82 houses in the current set of visualizations were determined by distributing the houses uniformly across the site and keeping them within the site boundary (the ditch). Within this boundary, the houses were placed off of the paths and no houses were placed in the designated plaza or chunkey court area. According to Morse (1998:99), the area between Mounds A, B, and C was probably a plaza area and was devoid of houses, burials, and other structures. But there are some reports that burials have been found in these areas,suggesting that they were not plazas. We have, for these examples, shown both the "plaza" and "chunkey court" as not having structures.

All of the early historic reports make it clear that there were extensive, well delineated and well known “trails” throughout North America. A good discussion of these travel routes can be seen for Georgia at https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/indian-trails, for Tennessee at http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/imagegallery.php?EntryID=T106. W. Myer in his “Indian Trails of the Southeast” in the 42nd Bureau of American Ethnography annual report (1928) summarized a great deal of data on trails (largely east of the Mississippi) and is online (from France!) at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k276550/f756.table. Manson (1998) has a useful article on trails as does Blakeslee and Blasing (1988). Village level travel routes (e.g. paths) are also shown in the John White watercolors. White traveled to "Virginia" in 1585 and was there for 13 months and made a number of detailed watercolors of Indian communities he visited. Images of the watercolors and engravings are available at this site depicting the Indian Village of Secotan. The specific path locations in the current Nodena Village images are completely hypothetical. It is logical to presume that there wore regular movement between key places in the village and the adjacent fields but beyond that we have no specific evidence.

Ceremonial Structures - What was the basis for the details in the ceremonial/mound area?

What was the basis for the location, height, and shape of mounds?

The location of the mounds was taken from the Nodena village plan (Morse 1989). Mound A (the larger mound) was described by Dr. Hampson as having the following characteristics in 1900: “40 steps (120 feet) long and from north to south 37 steps (111 feet) wide. It was 15 ½ feet tall. There was an apron or terrace 20 to 30 feet wide extending the length of the mound on the north side. The top of the mound was flat and was 40 feet long by 60 feet wide. To the northeast was a small mound about 2 feet high and 25 steps in diameter. To the northwest was a was a small round mound about 12 to 18 inches high, 15 steps in diameter. To the west and a little south of the large mound was a rather large rectangular flat mound, 42 steps from north to south and 37 steps from east to west and about 4 feet high. To the south and a little west was a small round mound about 3 feet high, 31 steps in diameter.” (1989:9).

Why are there stairs on the mounds?

Reports of “stairs” on mounds come from a number of sources. From the de Soto annals, for example, is a description of “an eight-foot wide ramp of earthen stairs steps secured by squared retaining timbers” (Nabokov and Easton 1989:93). Archaeological investigations at Hiwassee Island recovered stairs on the mound there.

What is the "plaza" and the "chunky playing court" and why did you locate them where you did?

According to Dr. Hampson a “chunkey playing court” at Nodena was south of the largest mound and was 150 feet long by 100 feet wide and had been covered with sand.” (Hampson 1989:9). Chunkey was a sport played by many historic groups that involved rolling a stone wheel-shaped “chunkey stone” and then players threw spears with the one closest to the stopping point of the rolling stone - but not touching – being the winner. In many ways it is quite similar to the Europe game of boccee ball. A description from James Adair (1775):

"The warriors have [a] . . . favorite game, called Chungke (Chunkey) . . . . They have a stone about two fingers broad at the edge, and two spans round: each party has a pole of eight feet long . . . . One of them hurls the stone on its edge, in as direct a line as he can, a considerable distance toward the middle of the other end of the square: when they have run a few yards, each darts his pole anointed with bear's oil, with a proper force, as near as he can guess in proportion to the motion of the stone—when this is the case, the person counts two . . . In this manner, the players will keep running most part of the day, at half speed, under the violent heat of the sun.""

More details are available at online at Indian Games hosted by Authorama

Morse (1989:99) also locates a of a “large plaza or public square” to the north and between Mounds A and B due to the absence of houses or burials and locates the chunkey field to the south of this area and Mound A. However, there have been some reports of burials being found in these areas - which would suggest that these areas are not plazas and/or chunkey courts. For this visualization we have elected to show both a plaza and chunky field. Large public plazas were common features of villages from this period and are document from many archeological sites and historic reports. Du Pratz, for example, describes a “parade ground” at the Grand Village of the Natchez that was “250 paces wide and 300 paces long” (Nabokov and Easton 1989:97). The specific locations in the visualization are based on the site map.

What is the basis for the size and construction details of the structures on the mounds?As reported by Dr. Hampson (1989:10) and further discussed in Mainfort (2005:23), three structures were found by Dr. Hampson on Mound A. The upper structure was described as rectangular and roughly 40 feet by 20 feet. In the site plans evaluated by Mainfort (2005:23-24) three rectangular structures are shown.

The largest is 40 east west x 20 north south and two smaller ones, also rectangular, are each roughly 22 x 13. However, Mainfort notes “the basis for Hampson’s drawing of the structure on the upper terrace of Mound A is not clear” (2005:24). Hampson did provide more details on the smaller structures. He describes them (Hampson 1989:13):

“… on the terrace we found the floors of two house sites. One of them was 27 inches deep. It was composed of burned clay form 2 to 4 inches thick, 22 feet long on the north side and 21 feet 4 inches on the south by 12 feet wide. Surrounding this was a row of postmolds up to 9 inches in diameter. The larger ones were at the corners. These were from 3 to 4 feet apart. The spaces between the posts had been filled with a wattle work of split cane plastered on both the inside and outside with clay. Some of the pieces of clay still retained the imprint of the cane.”

Similar structures on mounds have been reported historically, for example, Charlevoix 1761:256 states:

[The house] of the great chief is rough cast very handsomely in the inside: it is likewise larger and higher than the rest, being placed in a more elevated situation, and has no cabbins adjoining to it. It fronts a large square, which is none of the most regular, and looks to the north.

According to du Pratz, in 1718, the Natchez War Chief occupied a structure that was 30 long and 20 feet high. The walls were wattle-and-daub and there were no windows. Beautiful woven mats covered the inside walls. The roof was thatched with grass “clipped uniformly, and in this way, however high the wind may be, it can do nothing against the cabin. The coverings last twenty years without repairing” (quoted in Nabokov and Easton 1989:96).

Again from Charlevoix 1761:256 for the Natchez,

"The temple stands at the side of the chief's cabbin, facing the east, and at the extremity of the square. It is built of the same material, with the cabbins, but of a different shape, being an oblong square, forty feet in length, and twenty in breadth, with a very simple roof, in the same form as ours. At each extremity there is something like a weather-cock of wood, which has a very coarse resemblance of an eagle. The gate is in the middle of the length of the building, which has no other opening: on each side there are seats of stone. What is within is quite correspondent to this rustic outside. Three pieces of wood, joined at the extremity, and placed in a triangle, or rather at an equal distance from one another, take up almost the whole middle space of the temple, and burn slowly away. An Indian, whom they call keeper of the temple, is obliged to tend them, and to prevent their going out. If the weather is cold he may have a fire for himself, for he is not allowed to warm himself at this, which burns in honour of the sun ... Ornaments I saw none, nor anything indeed which could inform me that this was a temple. I saw only three or four boxes lying in disorder, with a few dry bones in them, and some wooden heads on the ground, of somewhat better workmanship than the eagles on the roof. In short, if it had not been for the fire, I should have believed this temple had been deserted for some tune, or that it had been lately plundered."

Benjamin Hawkins visiting the area described by Bartram some two decades (1798) later and provided these additional structural details (quoted in Pickett 1853 and accessible at History of Alabama, etc...in Google Books Online:

Choo-co-thluc-co, (big house,) the town house or public square, consists of four square buildings of one story, facing each other, forty by sixteen feet, eight feet pitch; the entrance at each corner. Each building is a wooden frame supported on posts set in the ground, covered with slabs, open in front like a piazza, divided into three rooms, the back and ends clayed up to the plates. Each division is divided lengthwise into two seats. The front, two feet high, extending back half way covered with reed mats or slabs; then a rise of one foot and it extends back, covered in like manner, to the side of the building. On these seats they lie or sit at pleasure.

The rank of the buildings which form the square:

1st. Mic-ul-gee in-too-pau, the Micco's cabin. This fronts the east, and is occupied by those of the highest rank. The centre of the building is always occupied by the Micco of the town, by the Agent for Indian Affairs, when he pays a visit to a town, by the Miccos of other towns, and by respectable white people. The division to the right is occupied by the Mic-ug-gee (Miccos, there being several so called in every town, from custom, the origin of which is unknown), and the councillors. These two classes give their advice in relation to war, and are, in fact, the principal councillors. The division to the left is occupied by the E-ne-hau-ulgee (people second in command, the head of whom is called by the traders second man). These have the direction of the public works appertaining to the town, such as the public buildings, building houses in town for new settlers, or working in the fields. They are particularly charged with the ceremony of the a-ce, (a decoction of the cassine yupon, called by the traders black drink,) under the direction of the Micco.

2nd.Tus-tun-nug-ul-gee in-too-pau, the warriors' cabin. This fronts the south. The head warrior sits at the end of the cabin, and in his division the great warriors sit beside each other. The next in rank sit in the centre division, and the young warriors in the third. The rise is regular by merit from the third to the first division. The Great Warrior, for II- that is the title of the head warrior, is appointed by the Micco and councillors from among the greatest war characters. When a young man is trained up and appears well qualified for the fatigues and hardships of war, and is promising, the Micco appoints him a governor, or, as the name imports, a leader (Is-te-puc-cau-chau), and if he distinguishes himself they elevate him to the centre cabin. A man who distinguishes himself repeatedly in warlike enterprises, arrives to the rank of the Great Leader (Is-te-puc-cau-chau-thlucco). This title, though greatly coveted, is seldom attained, as it requires a long course of years, and great and numerous successes in war….

3rd. Is-te-chaguc-ul-gee in-too-pau, the cabin og the beloved men. This fronts the north. Ther are a great many men who have been war leaders, and who, of various ranks, have become estimable in a long course of public service. They sit themselves on the right division of the cabin of the Micco, and are his councilors. The family of the Micco, and the great men who have distinguished themselves occupy this cabin of the Beloved Men.

4th. Hut-te-mau-hug-gee, the cabin of the young people and their associates. This fronts the west. The convention of the town The Micco, councillors and warriors meet every day in the public square, sit and drink of the black tea, talk of the news, the public and domestic concerns, smoke their pipes, and play Thla-chal-litch-cau (roll the bullet). Here all complaints are introduced, attended to and redressed

5th. Chooc-ofau-thluc-co, the rotundo or assembly room, called by the traders, "hot house." This is near the square, and is constructed after the following manner: Eight posts are driven into the ground, forming an octagon of thirty feet in diameter. They are twelve feet high, and large enough to support the roof. On these five or six logs are placed, of a side, drawn in as they rise. On these long poles or rafters, to suit the height of the building, are laid, the upper ends forming a point, and the lower ends projecting out six feet from the octagon, and resting on the posts, five feet high, placed in a circle round the octagon, with plates on them, to which the rafters are tied with splits. The rafters are near together, and fastened with splits. These are covered with clay, and that with pine bark. The wall, six feet from the octagon, is clayed up. They have a small door, with a small portico curved round for five or six feet, then into the house. The space between the octagon and wall is one entire sofa, where the visitors lie or sit at pleasure. It is covered with reed, mat or splits.

In 1843 the artist John Mix Stanley visited a Creek town and reported the following information on how the community was organized to construct these large ceremonial structures. He (1892:12) describes the town of Tuck-a-back-a-micco:

In his town is a building of rather a singular and peculiar construction, used during their annual busk or green-corn dances as a dancing-house. It is of a circular form, about sixty feet in diameter and thirty feet high, built of logs; and was planned by this man in the following manner : — He cut sticks in miniature of every log required in the construction of the building, and distributed them proportionately among the residents of the town, whose duty it was to cut logs corresponding with their sticks, and deliver them upon the ground appropriated for the building, at a given time. At the raising of the house, not a log was cut or changed from its original destination; all came together in their appropriate places, as intended by the designer. During the planning of this building, which occupied him six days, he did not partake of the least particle of food.

It is likely that the specifics (especially about the “lengths of logs”) was related to the presence of steel axes and other similar tools. Therefore, the precise details are probably not capable of being extrapolated “back” to the Nodena village but the general way in which a community can be organized may well be.

This material is available in: Portraits of North American Indians in Google Books Online

Why is one of the Mound structures shown as circular?

A round structure was reported by Dr Hampson on Mound B. Only limited excavation was conducted by Dr Hampson, but he believed that he found evidence for a round structure some 60 feet in diameter. Mainfort (2005:25) raises some questions about the strength of the evidence, noting that Hampson only exposed only a small part of the arcs and that the structure, if present, would be the largest structure excavated at Nodena. We have elected to represent this structure in the (re)creation but its presence should be considered tentative.

However, there were indeed round “ceremonial” structures of this size reported at various historic Indian villages. For example, a large circular structure used by the Cherokee was given this extended description from Bartram (1853:366-367) as reported in Bushnell (1919:60). The report also provides a perspective to the complex construction techniques that could be applied to any large structure.

The Cherokee town of Cowe (Kawi'yl, Mooney) stood on the banks of the Little Tennessee, about the mouth of Cowee Creek, in the present Macon County, North Carolina, among the beautiful hills and valleys of the southern Alleghenies (pi. 10, a). When visited by Bartram in the spring of 1776, the town consisted of about 100 dwellings, and here was a town house large enough to allow several hundred persons to gather within. This occupied the summit of an artificial mound some 20 feet in height. The building rose 30 feet higher, making the peak of the roof 50 feet above the surrounding area. Bartram's description of this structure is of much interest (op. cit., pp. 366-367):

"They first fix in the ground a circular range of posts or trunks of trees, about six feet high, at equal distances, which are notched at top, to receive into them from one to another, a range of beams or wall plates; within this is another circular order of very large and strong pillars, above twelve feet high, notched in like manner at top, to receive another range of wall plates; and within this is yet another or third range of stronger and higher pillars, but few in number, standing at a greater distance from each other; and lastly, in the centre stands a very strong pillar, which forms the pinnacle of the building, and to which the rafters are strengthened and bound together by cross beams and laths, which sustain the roof or covering, which is a layer of bark neatly placed, and tight enough to exclude the rain, and sometimes they cast a thin superficies of earth over all. There is but one large door, which serves at the same time to admit light from without and the smoke to escape when a fire is kindled; but as there is but a small fire kept, sufficient to give light at night, and that fed with dry small sound wood divested of its bark, there is but little smoke. All around the inside of the building, betwixt the second range of pillars and the wall, is a range of cabins or sophas, consisting of two or three steps, one above or behind the other, in theatrical order, where the assembly sit or lean down ; these sophas are covered with mats or carpets, very curiously made of thin splints of Ash or Oak, woven or platted together; near the great pillar in the centre the fire is kindled for light, near which the musicians seat themselves, and round about this the performers exhibit their dances and other shows at public festivals, which happen almost every night throughout the year."

Again from Bartram’s Travels (but this time quoted in Pickett 1851:100) and accessible at History of Alabama, etc... in Google Books Online we have this description of a circular “ceremonial” structure from the Creek:

The great council house in Auttose, was appropriated to much the same purpose as the square, but was more private. It was a vast conical building, capable of accommodating many hundred people. Those appointed to take care of it, daily swept it clean, and provided canes for fuel and to give lights. Besides using this rotundo for political purposes, of a private nature, the inhabitants of Auttose were accustomed to take their " black drink " in it. The officer who had charge of this ceremony, ordered the cacina tea to be prepared under an 1777 open shed opposite the door of the council house ; he directed bundles of dry cane to be brought in, which were previously split in pieces two feet long. "They were now placed obliquely across upon one another on the floor, forming a spiral line round about the great centre pillar, eighteen inches in thickness. This spiral line, spreading as it proceeded round and round, often repeated from right to left, every revolution increased its diameter, and at length extended to the distance of ten or twelve feet from the centre, according to the time the assembly was to continue." By the time these preparations were completed, it was night, and the assembly had taken their seats. The outer end of the spiral line was fired. It gradually crept round the centre pillar, with the course of the sun, feeding on the cane, and affording a bright and cheerful light. The aged Chiefs and warriors sat upon their cane sofas, which were elevated one above the other, and fixed against the back side of the house, opposite the door. The white people and Indians of confederate towns sat, in like order, on the left — a transverse range of pillars, supporting a thin clay wall, breast high, separating them. The King's seat was in front ; back of it were the seats of the head warriors, and those of a subordinate condition. Two middle-aged men now entered at the door, bearing large conch shells full of black drink. They advanced with slow, uniform and steady steps, with eyes elevated, and singing in a very low tone. Coming within a few feet of the King, they stopped, and rested their shells on little tables. Presently they took them up again, crossed each other, and advanced obsequiously. One presented his shell to the King, and the other to the principal man among the white audience. As soon as they raised them to their mouths, the attendants uttered two notes — hoo-ojah! and a-lu-yah! — which they spun out as long as they could hold their breath. As long as the notes continued, so long did the person drink or hold the shell to his mouth. In this manner all the assembly were served with the " black drink." But when the drinking begun, tobacco, contained in pouches made of the skins of the wild cat, otter, bear and rattlesnake, was distributed among the assembly, together with pipes, and a general smoking commenced. The King began first, with a few whifls from the great pipe, blowing it, ceremoniously, first towards the sun, next towards the four cardinal points, and then towards the white audience. Then the attendants passed this pipe to others of distinction. In this manner, these dignified and singular people occupied some hours in the night, until the spiral line of canes was consumed, which was a signal for retiring.

Why is there no wall/palisade on the mound around the buildings?

In many mound sites around the Eastern US there are wooden walls (palisades) that surround the structures on the mound tops. But there are many others that do not have such a palisade. Dr. Hampson’s excavations did not recover any evidence of a palisade and none is shown in the (re)creations.

Houses and Other Structures - What structures are present in the virtual village and why?

What was the basis for the size and shape of houses?

Excavations at Nodena by Morse exposed two square house foundations - one 17 feet (5.2 m) on a side and one-19 ft (5.7 m). Mainfort (2005) described his careful study of the site map prepared by Dr. Hampson. These maps showed detailed floor plans of 54 of the 66 houses. While Mainfort believes these plans to be somewhat “idealized,” they do provide some evidence for the house distributions and sizes. Scaling the house sizes from Mainfort’s published data (this should be seen as only an approximation), we could count 23 houses whose east-west dimension (typically the longest side) was between 10 and 17 feet. Twenty had the east-west dimension between 20 and 25 feet and four were longer than 25 feet on that side. Sixteen of the houses were essentially square with dimensions ranging from 10 x 10 to 13 x 13 feet. The larger houses were more rectangular in size with the longest axis running east to west. The Natchez had, according to Bushnell (1919:67) houses that were perfectly square, none less than 15 feet each way, and some 30 or more feet on a side.

In the visualizations, we have five base "floor plans" that are used throughout the site. The houses average 20X13 feet wide, and 20 feet in height

What was the basis for the appearance of the houses?

There are a number of sources for house construction and appearance. Some of the historic reports include: Charlevoix (1761:256):

The cabbins of the great village of the Natchez, the only one I have seen, are in the form of square pavilions, very low, and without windows. Their roofs are rounded pretty much in the same manner as an oven. Most of them are covered with the leaves and straw of maiz. Some of them are built of a sort of mud, which seemed tolerably good, and is covered outside and inside with very thin mats. … All the moveables I found in it were a bed of planks very narrow, and raised about two or three feet from the ground; probably when the chief lies down he spreads over it a matt, or the skin of some animal. . . . These cabbins have no vent for the smoke, notwithstanding those into which I entered were tolerably white.

What was the basis for your characterization of the wall surfaces and construction details of houses?

There is archeological, historic and traditional information on house construction. Houses at the contemporary Bradley archeological site are described (Morse and Morse 1983:286) as

… square in shape with upright post studs in individual holes or wall trenches. Split cane and cane or small-tree-limb lathing (wattle) provided a strong woven wall, which was then plastered with mud (daub) 5 or more cm thick. The roof was then shingled with thatch.

Wall construction of many square structures in the American Bottoms (earlier than Nodena) used red oak, willow, white oak, ash and hickory (Simon 2002). Most of the hardwoods were available at the American Bottoms bluff bases and would not be as accessible at Nodena where cypress and related species would be much more common. However, even at sites in the floodplain in the American Bottoms builders preferred oak, hickory and similar trees to the local floodplain wood types.

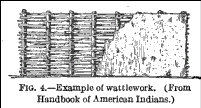

A drawing in Bushnell (1919:64) shows the construction details for a wattle and daub or wattlework wall. The image (and report) is available on the web in Native Villages and Village Sites East of the Mississippi in Google Books Online

Bushnell (1919:64) has this description:

Their house is nothing else than a cabin made of pieces of wood of the size of the leg, buried in the earth and fastened together with lianas, which are very flexible bands. These cabins are surrounded with mud walls without windows; the door is only from three to four feet in height. They are covered with bark of the cypress or the pine. A hole is left at the top of each gable-end to let the smoke out, for they make then fires in the middle of the cabins, which are a gunshot distance from each other. The inside is surrounded with cane beds raised from three to four feet from the ground. Heavy skins, such as those of the bear, buffalo, or deer, served as coverings; others were spread upon the "cane beds."

The Natchez had, according to Bushnell (1919:67), houses built in the following manner:

Hickory saplings about 4 inches in diameter were placed firmly in the ground at the four corners. Others, probably smaller, were arranged about 15 inches apart in lines between the corner posts, forming the walls of the structure. Poles were then fastened on the inside of these in a horizontal position, bound and held by split canes. The four corner poles, which were as much as 20 feet in length, were bent inward, thus meeting in the center of the frame, and were fastened. The poles along the sides were likewise bent in and so secured to the four principal supports. The frame was then covered with a "mortar of mud mixed with Spanish beard, with which they fill up all the chinks, leaving no opening but the door, and the mud they cover both outside and inside with mats made of the splits of cane. The roof is thatched with turf and straw intermixed, and over all is laid a mat of canes, which is fastened to the tops of the walls by the creeping plant. These huts will last 20 years without any repairs." (Du Pratz, (1), II, pp. 224- 225.) Within the habitations raised platforms, a foot or more above the ground, served as sleeping places. These were covered with heavy skins during the cold season, and often with mats during the summer. Bags filled with Spanish moss were used on the beds. Low stools were seen by Du Pratz but were seldom used.

Bushnell (1919:69) also quotes James Adair (1775):

“… who spent many years as a trader among the southern Indians, and whose work treats principally of the Chickasaw among whom he lived the greater part of the time, has left a detailed account of the manner in which they constructed their different houses. (Adair 1775 417-421.) The whole village aided in the work, "and frequently the nearest of their tribe in neighboring towns, assist one another. . . In one day, they build, daub with their tough mortar mixed with dry grass, and thoroughly finish, a good commodious house. They first trace the dimensions of the intended fabric, and every one has his task prescribed him after the exactest manner. . . . For their summer houses, they generally fix strong posts of pitch-pine deep in the ground, which will last for several ages. The posts being of equal height were notched to hold the wall plates. A larger post was then placed in the middle of each gable end, and another in the center of the house to mark the position of the partition. The frame was completed by using many small split saplings and some larger logs, all of which were secured by tying. The outside was made of pine, or cypress clap-boards, which they can split readily; and crown the work with the bark of the same trees, all of a proper length and breadth, which they had before provided. The covering was held in place by split saplings, tied to the frame at the ends."

Archeological evidence from a very large sample of excavated structures from the American Bottoms suggest that wall thickness of houses otherwise similar to those at Nodena – which is in the range of 20-30 cm (Hargrave 1991:222).

What was the basis for your (re)creation of the roof shapes and forms?

There is relatively little archeological evidence from the Nodena site for the specifics of roof structures except the note of “roof supports” from the 1973 excavations (Morse 1989:102) but there is a great deal of archeological information from other sites and areas. While from an earlier period there are a number of well documented burned structures from the American Bottoms area (near modern day St Louis). As described in Simon (2002), the construction materials were generally consistent. Burned thatch was found at 11 locations and was commonly longer grass stems, giant cane and small woody and twigs – often willow. Roof shapes were hip or gabled based on the presence of central post or posts. One example of a recreation of a Mississippian house at Toqua TN can be seen a the Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee site.

What was the basis for the exterior color(s) of the structures?

In our first cycle of visualization we have elected to show the walls of all the structures in various shades of earth tones. These colors would be the result of using a typical clay for the wattle and daub surface. In future examples, however, we plan to offer a wider range of colors and decorations. Historic reports indicate that the use of color and decorations was common. Busnell 1919:80, for example, says:

The custom of whitewashing the various structures was evidently quite general among the southern Indians, and several materials were used, including decayed shells, white clay, and in later days lime was prepared by burning oyster and clam shells. To what extent the houses were otherwise decorated is not known, although it was done among the Creeks and probably followed to some degree by the other tribes of the region. Bartram, when replying to a question respecting this phase of art among the Indians, wrote: " The paintings which I observed among the Creeks were commonly on the clay-plastered walls of their houses, particularly on the walls of the houses comprising the Public Square . . . The walls are plastered very smooth with red clay, then the figures or symbols are drawn with white clay, paste, or chalk; and if the walls are plastered with clay of a whitish or stone color, then the figures are drawn with red, brown, or bluish chalk or paste." (Bartram, W., (1), p. 18.) The drawings represented many forms of animal and plant life.

What are the small house-like structures on "stilts?"

These are “corn cribs” – storage facilities for corn. Across the continent many Indian communities grew and stored substantial amounts of corn. In some areas these were stored in deep pits but in location like eastern Arkansas the soil properties and moisture made this option impossible. As a result, structures were built that protected the corn from both possible flooding as well as destruction from animals. In excavations conducted in 1973 Morse uncovered some 45 cobs of maize in Feature 8. The maize was burned and the cobs were largely intact leading Morse (1973:8) to propose that an above ground corn crib (or granary) was present. Mainfort et al (1997:113) are not as confident that this was a corn crib as no evidence of daub was found. They also suggest that corn was not stored in its cob form but as parched corn. We actually have some early photographs of some example of corn cribs - there are some from Chief Long Hat’s family compound near Binger, OK taken in 1870 by William Soule (see examples a the Texas Beyond History website). Historic reports also describe above ground corn storage. Spanish reports from the immediate area (but some 100-150 years later) describe corn cribs as “houses raised up on four posts, timbered like a loft and the floor of cane” (Elvas 1993:75, quoted in Mainfort et al). A modern recreation from the Etowah Gallery can be seen online in the Georgia Lost Worlds website.

What are the shorter pole structures with objects on them?

These are drying racks. A drying rack was used to dry (or sometimes smoke) both animal and vegetable material to preserve it. They generally consisted of four (or more) uprights and a rectangular grid of poles upon which the material to be dried (or smoked) was placed. Some historical drawings include those of John White and De Bry at http://www.virtualjamestown.org/images/white_debry_html/plate44.html

An example from LeMoyne showing Timucua Indians smoking game on a rack can be seen at: http://pelotes.jea.com/NativeAmerican/LeMoyne/drying%20rack.gif with an accessible and interesting critical discussion on it and other images at http://pelotes.jea.com/leMoyne.htm and in this National Humanities Center Article.

Wissler has a drawing of a Blackfoot drying rack (1920:26) -- available in his book titled North American Indians of the Plains hosted by Google Books Online.

Jenks (1900:1068) illustrates a section of drying rack used for drying wild rice in Plate 75 -- available on line at Tusayan Migration Traditions in Google Books Online

What are the pole structures that are taller and have grass or cane on them?

These are variously referred to as “summer kitchens,” “shade arbors,” “brush arbors” or “ramadas,” and they are simply shaded areas where it is possible to work – typically during the summer heat. They were constructed by setting up a series of vertical poles, taller than a person, attaching cross poles and then covering the framework with branches, grass or other materials that would provide shade. Sometimes the sides had intermediate horizontal poles at roughly waist height that served as storage or work surfaces. The great majority of historic references to these structures come from areas west of the Mississippi Valley (especially the Caddoan area and Great Plains and beyond) but there are also many historic accounts of them in the southeast (Pezzoni 1997). Of particular interest is this reference which links the Indian use of brush arbors to their important role in African American religion during the pre-Civil War period. As described by Minges (2002:462):

Native Americans also played roles in the development of the African American churches through supporting the "invisible institution." A prominent aspect of slave religion was the "brush arbor." These brush arbors, hastily constructed "churches" made of a lean-to of tree limbs and branches, had been a prominent part of the southeastern traditional religion. The brush arbor architecture that became a critical part of the "camp-meetings" of the Second Great Awakening was borrowed from the architecture of the "stomp ground" of southeastern traditional religious practices. That Native Americans supported the invisible institution is evidenced in the slave narratives: "Master Frank wasn't no Christian but he would help build brush arbors fer us to have church under and we sho would have big meetings I'll tell you." (available at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_indian_quarterly/v025/25.3minges.html).

Ramadas can been seen prominently in photos from Long Hat’s village (http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/tejas/fundamentals/life.html).

These are hide stretchers. They were used to help clean and process deer and other hides. A detailed description on the general process is from the Milwaukee Public Museum (on-line at http://www.mpm.edu/WIRP/ICW-11.html): The hide was then hung on a line, the wrinkles pulled out, and bullet holes sewn up with needle and thread. Along the edge of the hide, holes were cut at intervals of three to four inches and a cord was passed through one hole and out the next all the way around the skin. The holes and the cord allowed easy suspension on the stretching frame. Every tanner had one of these frames set up permanently in a shady spot in her yard. The frame consisted of two posts set into the ground five to six feet apart with horizontal crossposts tied on about three and a half feet apart. A cord was attached to the neck of the hide and fastened to one of the upright posts of the frame. The tail portion was attached to the other upright, and the legs were tied with cords to each of the four corners of the frame. A long cord was passed through the edge lacing and then around the frame and the hide itself could be drawn taut within the rectangle. A stretching tool made of wood with a convex blunt edge was strongly pushed and stroked in a sweeping motion across the hide, causing it to stretch. After a few minutes of this, the suspension cords needed tightening. This process was repeated over and over until the hide had reached its maximum size. During all this time the hide was drying, and it had to be completely dry before it could be removed from the frame. The frame was always set up in the shade so the hide would not dry too rapidly, otherwise it would shrink and stiffen. Depending on the weather, the hide stayed on the frame for about an hour to an hour and a half. When the woman removed it, the hide was pure white and very soft to the touch.

Accessible information on the overall process is at http://mdc.mo.gov/teacher/highered/crafts/craft20.htmIn addition to stretching, hide smoking (or smudging) was probably practiced at Nodena. In later versions we will add some of these features to the images.

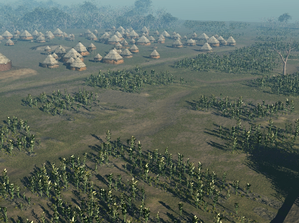

Corn Fields and Vegetation- What was the basis for the presence of vegetation in the visualizations?

What was the relationship between the village and the fields around it?

Multiple images show the agricultural fields near the Nodena village and the village in the background. The Nodena people raised a number of crops, principally corn, beans and squash. Though ancestral to the corn of today, the types of corn grown 500 years ago were generally smaller plants - but some grew to as tall as 10 feet. Beans and squash plants were often planted among the corn, though were chosen not to be present the visualizations presented here.

According to Hammett (1997:197):

The centers of habitation sites in the eastern Woodlands were typically composed of domestic structures and small garden plots similar to the “dooryard” gardens found throughout much of Latin America (Chavero and Averez-Buylla Roces 1988; Kimber 1973). Adjacent to the core of the community were fields of crops, interlaced with old fields lying fallow. In these open old-field areas perennial crops such as berries, fruit and nut trees and several economically valuable “weeds” typically thrived (Bartram 1973). A wooded zone beyond the fields served as an extremely valuable combination of orchard, hunting park, and wood lot, supplying the local inhabitants with many of their basic needs and a gradual territorial margin.

Note that in the Mississippi Valley, around the Nodena Village, it is likely that frequent flooding may have meant that there was no need to have fallow fields.

What was the basis for the representation of the corn field?

We have both historic and archeological evidence for the layout and character of corn fields. Most of the early European travelers described the extensive corn fields that they encountered as they neared any substantial village but they only provide general descriptions.

One very useful early historic source is the illustrations of John White. White traveled to “Virginia” in 1585 and was there for 13 months. Again, it should be noted that evidence from the east coast of the US and about a 100 years later than Nodena should not be used uncritically, but White’s watercolors and the engravings made from them do provide some useful information. In his “Village of Secoton” watercolor White shows small well delimited fields immediately beside the villages. Images of the watercolors and engravings are available at http://www.virtualjamestown.org/images/white_debry_html/plate35.html

As discussed in Hulton and Quinn (1964) – and available on the web at http://www.virtualjamestown.org/images/white_debry_html/white.html#s38 – White’s watercolor shows:

To the right of the path and street are three cornfields each at a different stage of growth. The top field of ripe maize contains a small hut, open at one side, which may shelter a seated figure and is mounted on a platform with four legs. A path to the right separates this field from the two lower ones in which crops of unripe and very young maize are growing. The last has faint indications perhaps representing hills around the bases of the plants. To the left of the unripe maize is a house with a small fenced yard before the door which is in the centre of the end wall. The houses to the left of the road are set among (or near to) birch-like trees

It has been stated that this scene was probably drawn by White on July 15-16th, 1585. The three stages of maize shown agree well with this date, since, according to Barlowe, the Carolina Algonkians planted three crops per year, in May (harvested in July), June (harvested in August), and July (harvested in September). The ripe maize shown may be the variety which, according to Hariot, was 10 feet high when ripe at fourteen weeks (there were two other varieties which ripened in ten to twelve weeks, when they were 6-7 feet tall).

Another of White’s images, “Village of Pomeiooc,”also shows fields in very close relationship to that village.

The 1917 publication Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden is from western Minnesota but has early photos and drawings showing many garden/field details. In the sketch maps of the fields they are shown as rather small “plots,” each associated with an individual or family group. The White watercolor appears to show a somewhat similar plot character.

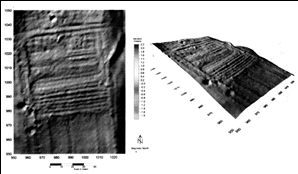

We have shown the fields as “raised” or ridged, with the corn planted in continuous ridges. Raised and ridged fields are found in archeological excavations from Ocmulgee Site (GA) where the ridges were around 20 cm high and 30-50 cm apart (Kelley 1938:10-11). Microtopographic data from the Litka Site (13OB31) where the surface has remained undamaged also clearly shows ridges. (Image courtesy: Office of State Archaeologist, University of Iowa, Steve Lensink and Lynn Alex)

Early historic reports of remnant ridged fields in areas such as the Ocmulgee River describe what appear to be more or less continuous fields extending for some two miles from the location of an abandoned village and in other sections of the report fields are described as extending for 15-20 miles up and down the river (Bartram 1928:68). This is also consistent with the early Spanish reports who describe “very large fields among the margins of the rivers and streams” throughout Northeastern Arkansas (Hudson 1997:288).

that there have been changes to the surface over the centuries, the data is still very useful. The soils mapped in the immediate location of the Nodena village, and for some distance to the south-east and north-west are (relatively) well drained soils on what may be a relic levee or point bar [link to soil map image?]. Beyond this to the east the ground slopes off to a slough and to the west was Young’s Lake, which was drained around 1900 (Mainfort 2003). High resolution elevation data that was developed for entire state in 2006 by the Arkansas Geographic Information Office and available at GeoStor shows a pattern that is very similar to the soils data and indicates that the village area is on the highest ground in the area with lower elevations corresponding to the more poorly drained soils.

We have chosen, therefore, to show the fields around the Nodena Village as an extensive series of individual plots to the west of the village in the area covered by the images and covering the entire well drained soil area but not as a single large “field.”

The density and character of corn in the fields is a matter of some discussion. The watercolors of White show tall corn (ca 10ft) in dense fields and it is presumed that this watercolor reflects a July 1585 date (Barlow in Quinn 1955). We have elected to show a somewhat less dense distribution and an earlier date in the year so that the plants are not shown with tassles.

Gartner (2003) in Raised Field Landscapes of Native North America is another very useful source on this topic and has many details and images of these types of fields and their characteristics.

Benjamin Hawkins described a Creek field in late 1796 in Georgia in the following:

I chose the river path that I might have a view of the Indian fields, their mode of culture and the quality of the lands. The first 4 miles were high and open sound low grounds, subject to inundations only in the seasons of floods which happen once in 15 or 16 years, the river is also subject to annual overflowings, but always in the winter season, generally in March; the next 8 miles is mostly canebrake land, very rich, much of it under cultivation, the corn planted in hills, not regular, about 5 feet from each other, and from 5 to 10 stalks in a hill, near every small division of corn they have a patch of beans stuck with cane. The margins on the river under cultivation is from one hundred to 200 yards wide, then the land becomes a rich swamp for 400 to 600 yards, this when reclaimed must be valuable for rice or corn, the river never subject to freshes in the spring or summer.

This text can be viewed at http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cmamcrk4/crkhk1.html

The specific visual properties of the corn plants in the images are shown in a generic form and do NOT represent specific plant types.

Was there a possible watchers platform in the field and what did it look like?

Field watcher platforms are platforms in or near the fields that are places for individuals (often children or women) to serve as guards for the crops. They would serve to scare off animals and birds and could raise the alarm if unfriendly people appeared. Such watcher platforms are shown in the early water colors of White especially the “Indian Village of Secton” discussed above. A lengthy discussion and a sketch of a watchers platform are also found the Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden. A similar sketch example of a watchers platform is shown in Plate 5 of Schoolcraft 1851(III) – representing a Mdewakanton platform in eastern Minnesota.

Why have you shown isolated trees in the field and what was your basis for the details of the forest around the site?

The nature of the trees and forest in the area of the Nodena Village was the result of the area’s natural conditions as well as 1,000s of years of “forest management” by the inhabitants of the area. It has become clear in the last decades that the Native Americans actively managed the forest throughout the continent. Selected trees were girdled and left standing and the windfalls served a firewood, nut and fruit bearing trees were left. See Delcourt and Delcourt (2004:70), Munson (1986) and Black and Abrams (2001) for more on managing the forests to improve nut harvest. We have elected to show isolated nut and fruit trees in areas around the fields.

On a regular basis the forest floor was burned (Hammett 1997:199) though such burning in the Mississippi Valley would have been restricted by standing water. Many Indian communities in the southeastern US burned their fields in late winter to clear them of weeds and add nutrients to the soil (Hudson 1997:123), another area that was typically burned were cane brakes.

Spanish explorers in Arkansas in 1543 described many open areas where horses could be ridden at a full gallop. They found large pecan trees, mulberry and persimmon scattered throughout open fields. “In clearing trees from land for farming, the Indians evidently spared nut and fruit trees “(Hudson 1997:288-9). Hudson goes on to say that many areas had trees “as if tended in orchards or gardens.” Other areas around Nodena were swampy and the Spanish reports traveling through many areas in water that was waist deep. In some smaller areas wooden bridges had been built across the swamps or sloughs. There were only capable of being traversed on foot as they consisted of logs lashed form tree to tree and a second as a “hand rail” above.

The soils and elevation data (discussed in more detail in the earlier sections of the FAQ on the fields) has been used to determine where the areas for the agricultural fields and where the swampy area would be located. Lower poorly-drained areas are immediately adjacent to the village boundary to the east and to the northeast. If the vegetation was unaltered these locations would very likely had cypress swamp vegetation. However, it seems likely that the need for fire wood and the potential desire for increased security would have meant that the trees closest to the site would have been girdled and killed. We have elected to show some cypress swamp forest in these areas to provide a visual indication of the presence of that vegetation. In the next phase of the visualization we plan to widen the area that will be considered and plan to show the swamp area nearest the site with girdled trees and those at a greater distance with full vegetation.